‘What are Hamlet's authentic motives? We are not permitted to know.’

- Harold Bloom

To my readers, I ask that you:

‘Season your admiration for awhile

With an attent ear.’

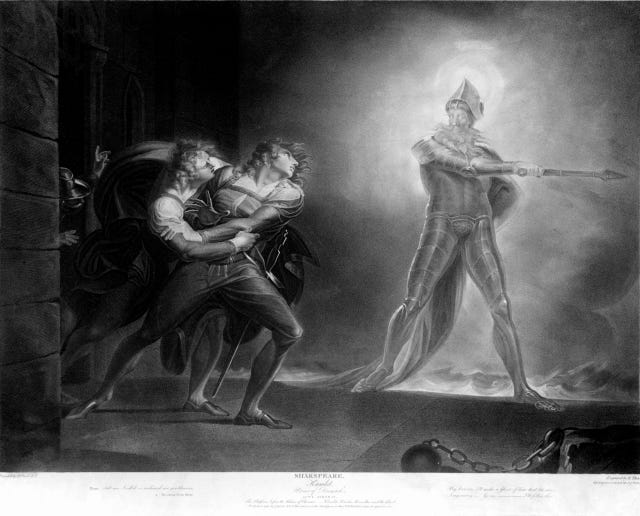

An attent eye will do. The Tragedy of Hamlet begins with the Prince of Denmark encountering the ghost of his late father, who informs him that:

‘The serpent that did sting thy father’s life

Now wears his crown.’

The implications are horrifying. King Claudius, who married Hamlet’s widowed mother, himself dealt the fatal blow to the former ruler. The fallout from this revelation is the substance of this play. In between the chaos, Hamlet considers a range of philosophical questions.

Harold Bloom observed that Hamlet's problem was not that he thought too much, but that he thought too well. As a result, he thought his way to the truth. Christ's crucifixion serves as a caution to those who try to do the same: it can only result in death, whether that be physical or metaphorical.

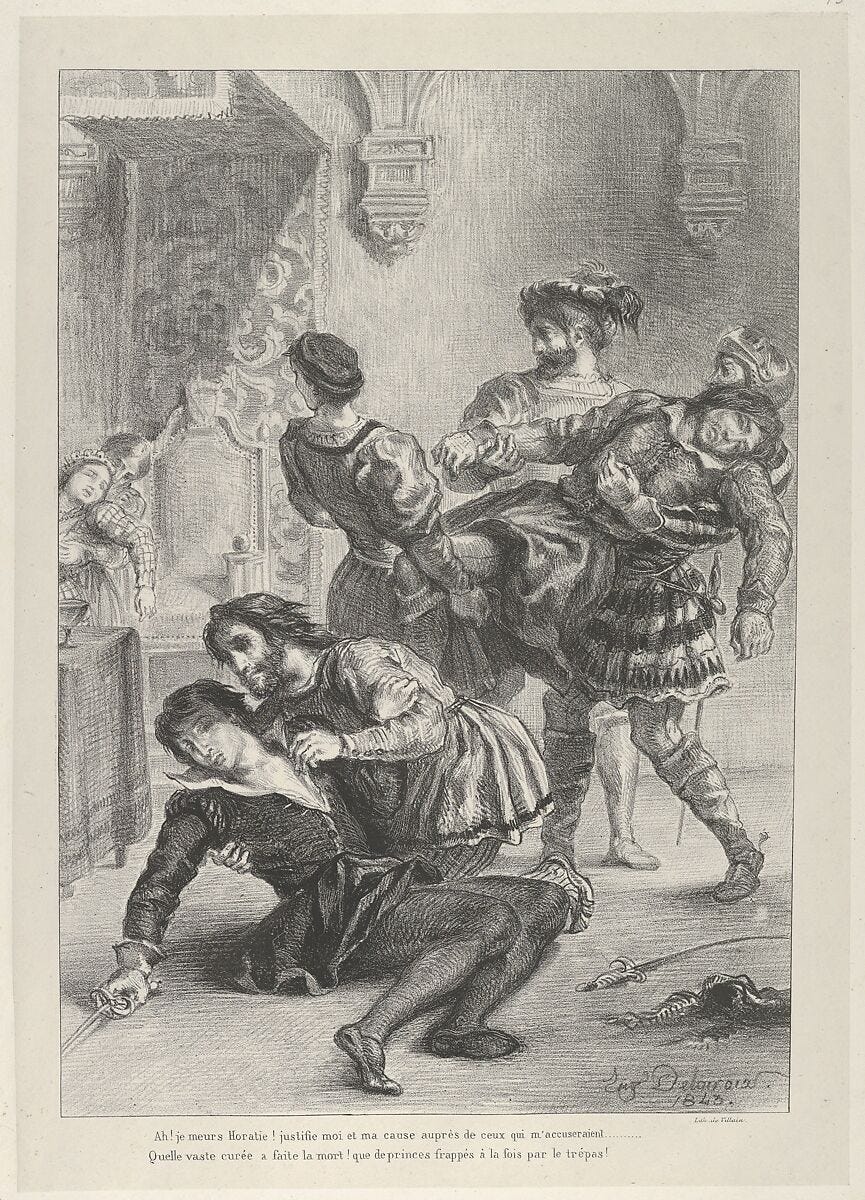

Hamlet’s death seems to prove me right. After discovering, with dreadful certainty, that Claudius murdered his father, he begins to wonder whether he should take his own life. He then loses his mind.

‘His madness is poor Hamlet’s enemy.’

Madness, however, is not the foe that claims his life. Indeed, after the young Dane killed Polonius, Laertes, his son, avenged his father. Had Hamlet and Laertes not known the true causes of their fathers’ deaths, had they fallen for lies, both would have lived. Perhaps this is why Bloom suggested that ‘a great unwisdom ultimately is better for us than the emptiness of truth.’

We return to the question of Hamlet’s death. All of us are familiar with his ‘To be, or not to be’ monologue. For some, it is a contemplation on the merits of self-slaughter. For Harold Bloom, Hamlet was brooding upon the limits of our wills. I remain ambivalent, and the correct interpretation of that passage is not my concern here.

‘If it be now,

'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be

now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the

readiness is all.’

Readiness here means willingness. In Matthew 26, Jesus asks his disciples to watch over him, but they quickly fall asleep. Understanding their frailty, He quips ‘the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak’ (New International Version). The Geneva Bible, which Shakespeare used, renders the verse thus: ‘the spirit is ready, but the flesh is weak.’

Therefore, ‘the readiness is all’ should read ‘the willingness is all.’

Hamlet is telling us that if death comes now, it will not come later. If it will not come later, then it will come now. If it does not come now, then it will certainly come later: all that matters is our willingness to confront it. The readiness is all.

At the end, Hamlet seems ready. Fortinbras laments ‘with sorrow I embrace my fortune’, but there does not appear to be any sorrow in Hamlet’s embrace. He is resolute. Flights of angels sing him to his rest.

‘The rest is silence.’